Organizational Steps in the Development of Black Seventh-day Adventist Ministry in the Southern Union

The January 2, 1946, issue of Southern Tidings featured an article by Elder Earl F. Hackman, Union president, which announced the organization of two new conferences: the South Atlantic Conference and South Central Conference. This year, these two conferences are celebrating 80 years of growth and ministry.

This article examines the social location of Black members and workers within the Seventh-day Adventist Church before 1946. It also discusses the organizational progress of Black Seventh-day Adventists in the Southern Union that has led to this historic celebration.

Divergences from Southern Tidings style in this article reflect and honor the eras and their documented minutes from which information was gleaned.

Early Members, Churches, and Pastors

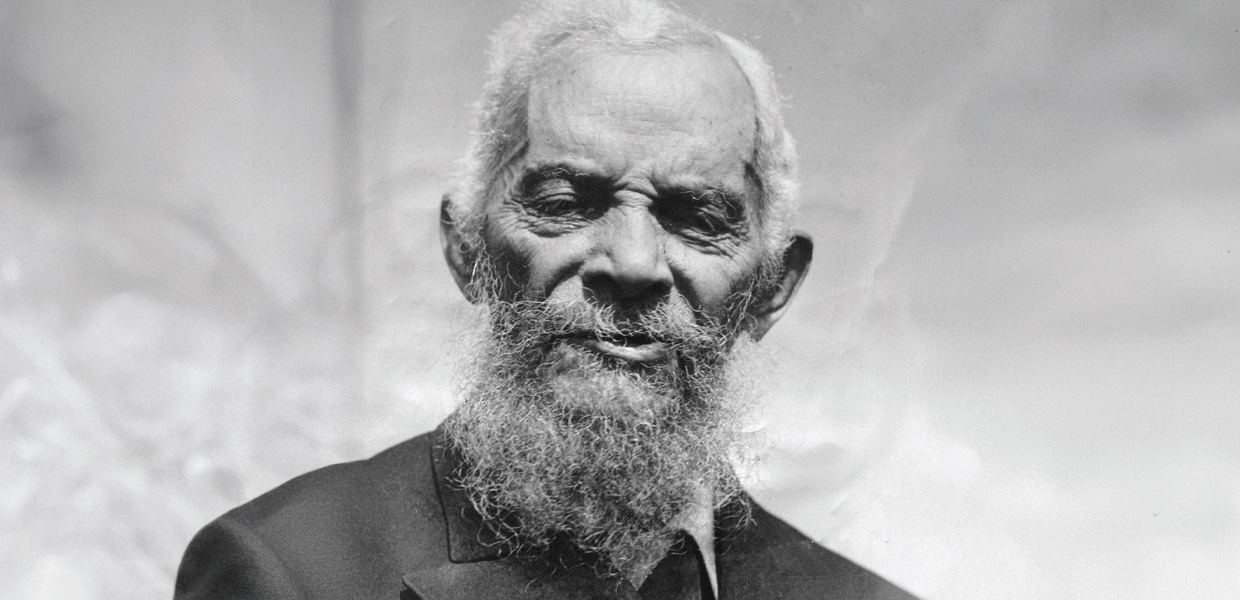

Harry Lowe, baptized by Elbert B. Lane at Edgefield Junction, Tennessee, in 1871, is believed to be the first Black Seventh-day Adventist in the Southern Union territory. He was a member of the biracial church Lane organized in 1873. In 1883, due to increasing racial tensions in the South, Samuel Fulton, president of the Tennessee Conference, separated the ten Black members of the church into a separate company with Harry Lowe as their pastor (Reynolds, We Have Tomorrow, 1984, p. 109). Though disappointed by segregation, they held onto Jesus, and, on November 9, 1886, became the first Seventh-day Adventist Church composed of African Americans (ibid, p. 109).

Other Blacks in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas began to join the Church. In the minutes of the November 8, 1883, General Conference session report, “Elder J. O. Corliss gave a statement of the condition and wants of the South Atlantic Mission. There are in this mission two hundred and sixty-seven white Sabbath-keepers and twenty colored,” (GCB 1863-1883, p. 230).

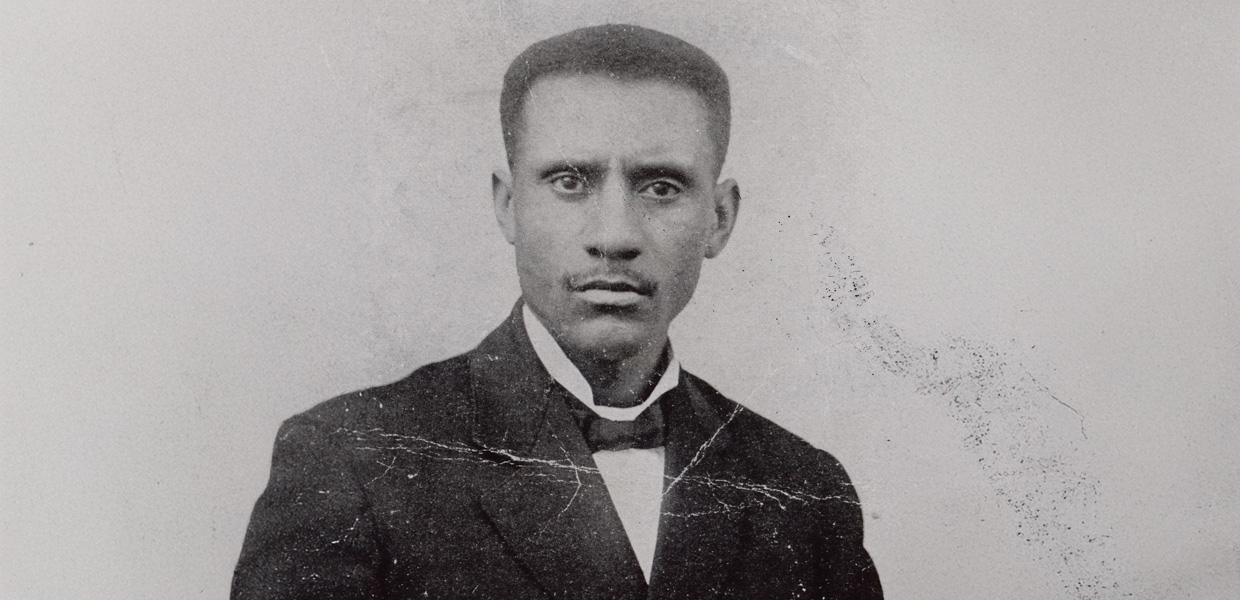

In the late 1880s, pastors Charles M. Kinney and Alonzo Barry began preaching in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Kentucky. Later, in 1896, pastor M. L. Ivory in Florida reported doing evangelism in Orlando, Sanford, Palatka, Windsor, Gainesville, Waldo, Jackson, and Punta Gorda (“South Atlantic Conference,” SDAE, 1996).

A handwritten note by Elder Charles M. Kinney lists the first five Black churches: Edgefield Junction, organized in 1883; Louisville, Kentucky, by Elder Alonzo Barry on February 16, 1890; Bowling Green, Kentucky, on June 13, 1891; New Orleans, Louisiana, on June 4, 1892; and Nashville, Tennessee, on September 15-16, 1894 (Marshall and Norman, A Star Gives Light, 1984, p. 26).

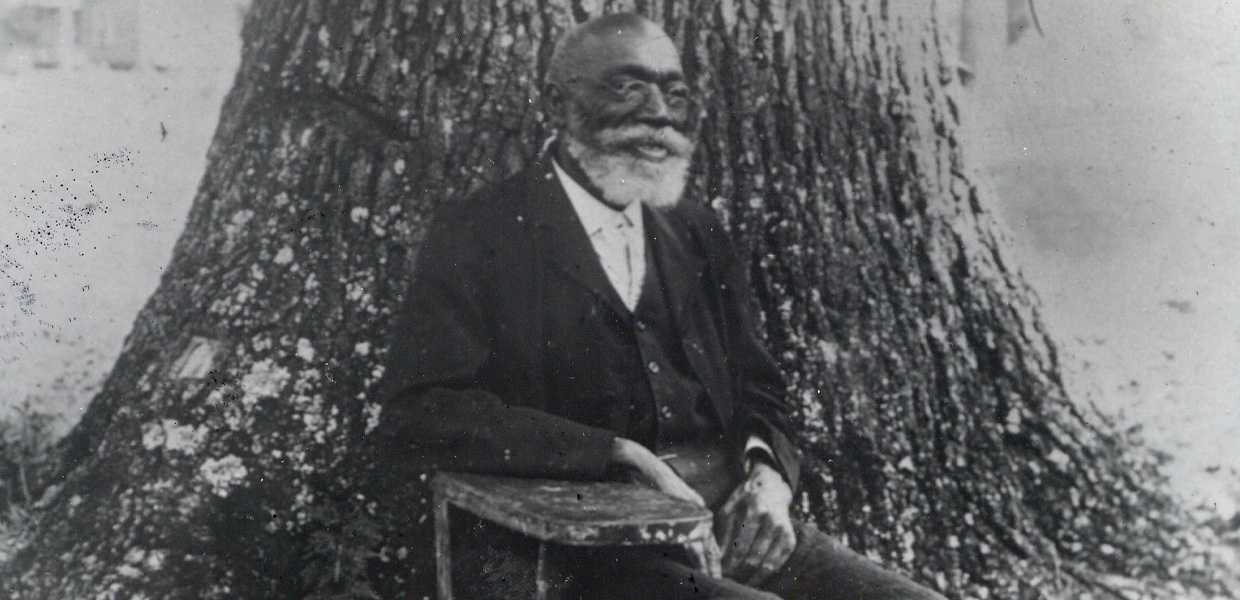

Over the next decade or so, Taswell B. Buckner, Peter M. Boyd, Joseph H. Laurence, George E. Peters, William H. Sebastian, Matthew C. Strachan, Franklin G. Warnick, and Thomas Murphy joined the ranks of Adventist pastors of African descent.

These pastors worked diligently despite facing racism from social conservatives both in society and within the church. Elder Charles M. Kinney addressed this issue on October 2, 1889, at a meeting led by Robert M. Kilgore. He started his remarks and suggestions for resolving the problem by stating, “This question [of segregation] is one of great embarrassment and humiliation, and not only to me, but to my people also.” He shared his belief that the everlasting Gospel preached under the third angels message “has the power in it to eliminate or remove this race prejudice upon the part of those who get hold of the truth.” Kinney then presented 12 points that could lead to a solution that would “be pleasing to God,” (See Rock. Protest and Progress, 2018, pp. 13-16 and Appendix 5).

Edson White and the Southern Missionary Society

James Edson White traveled to Mississippi in 1895 aboard the Morning Star steamer and started schools as a way to do evangelism among Black people. From these schools, he aimed to establish churches. The year after White’s arrival, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Plessy v. Ferguson case. This decision overturned an 1875 Civil Rights Act that had made it a crime to deny the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement based on race or color. It also upheld a Louisiana law that permitted “equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races.”

But under these challenging social conditions, which affected not only Black communities but also Edson White and his team, they faithfully worked to build and raise up schools and churches in Vicksburg, Yazoo City, Natchez, Columbus, and numerous other towns in Mississippi. To promote and oversee his work, Edson White published the Gospel Herald and formed the Southern Missionary Society. By 1898, “The society, which had begun in Mississippi and had extended its activities to Tennessee, became responsible for the Black work in all the territory south of and including Kentucky and east of the Mississippi River,” Gospel Herald, May 1898, p. 7.

Ellen White visited her son, Edson, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, where she dedicated the new Black church and school before attending the April 1901 General Conference. En route to General Conference, she stopped to see the members in Memphis, Tennessee, and toured Nashville. In Nashville, she met with local leaders and learned about the needs of General District #2, which covered nine Southern states (White, Arthur. Ellen G. White: The Early Elmshaven Years, p. 65).

The delegates at the 1901 General Conference Session voted to establish unions, which represented a new administrative level in the North American Division. The territory previously known as General Conference District #2 was voted to become the Southern Union, the first Union on April 9 and began operations on May 1, 1901.

Camp Meetings and Institutions

Just after the turn of the century, meetings advertised as “colored camp meeting” began to be held in various locations. The first took place in Edgefield Junction in 1901, and another was held in 1903 at Plant City, Florida. Soon, most, if not all, the conferences in the Union held separate annual colored camp meetings, often in the same city as the White camp meeting.

During these years, the Black work expanded to include Oakwood Manual Training School (November 1896), the Nashville Colored Clinic (1901), Rock City Sanitarium (February 1909), and Oakwood Sanitarium (1911).

Reporting on the growth of the work for Blacks, Pastor Sydney Scott wrote in the Gospel Herald in July 1907, p. 26: “Fifteen years ago there were not over twenty colored Seventh-day Adventists south of the Mason-Dixon line, but today there are seven hundred. Twelve years ago there was only one colored Seventh-day Adventist church; today there are fifty, not counting those in Africa or the West Indies. Fourteen years ago, there were only two colored ministers; today, there are forty-five in the United States, and counting those in Africa and the West Indies, the number will reach sixty. The tithes of the colored people last year in the United States amounted to $5,000; fifteen years ago, it was not over $50. One year ago there was no sanitarium for colored people in the whole denomination where modern methods were used; today there is one in Birmingham Alabama, with Dr. L. C. Isbell as chief physician. Thirteen years ago, we had no colored Seventh-day Adventist physician; today we have five practicing using modern methods.”

The Southern Union Divides

In 1908, Southern Union was divided into Southeastern and Southern Union conferences. The territory of the new Southeastern Union included North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The Southern Union included Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Louisiana.

Negro Mission Department

At the 1909 General Conference session, action was taken to organize the work for Blacks in the Southern, Southeastern, and Southwestern Union Conferences on a mission basis within each union.

The Southern Union Conference, from which the Southeastern Union Conference had been separated in 1908, established the Southern Union Negro Mission, operating under the name of the Southern Missionary Society. This took “over all work and workers for the colored people heretofore maintained by the several local conferences and by the Union Conference, excepting the school at Oakwood,” and received the tithe and other funds from all the Black churches in the area (Gospel Herald, June 1909, p. 27; cf. November 1909, p. 45).

In 1909, the Negro Department of the Southeastern Union was established with Matthew C. Strachan serving as Field Secretary. M. C. Strachan (South Carolina Conference), Sydney Scott (North Carolina Conference), J. W. Manns (Florida Conference), William H. Maynor (Cumberland Conference), and R. L. Williams (Georgia) were appointed as superintendents of local Negro missions within the state conferences (Field Tidings, vol. 2, No. 6, March 2, 1910, p. 1. See also Field Tidings, January 10, 1912, pp. 2-3).

The Negro missions, later known as the Colored departments (1927), were separate parallel organizations within the Unions and state conferences that oversaw the colored members, churches, and pastors. The Negro Missions had their own executive committee composed of White conference officers serving as ex officio members, along with selected Black pastors and sometimes other White or Black laypeople.

Because decisions regarding the Black work were often made by all-White executive committees and then communicated to the Black members, a resolution was adopted in 1912 recommending that at least one colored worker be included on the committees at the Union Conference sessions that addressed issues related to the Negro Mission.

Evangelism

Under the Negro Department, Black membership started to grow between 1909 and 1918, but saw significant increases when W. H. Green became the first African American to lead the General Conference Negro Department. Some of the leading evangelists included John G. Thomas, who later became a Southern Union evangelist; Matthew C. Strachan; John F. Greene; George E. Peters, who baptized 232 in Tampa; John W. Manns, who baptized 125 in Savannah; Matthew Strachan; Sydney Scott; Joseph H. Laurence; Taswell B. Buckner; and F. S. Keitts.

Several of these men were designated Union Mission evangelists. They included George E. Peters (1916-1918), John G. Thomas (1933-1937), and F. S. Keitts (1938-1941). Other early leading evangelists were Edward E. Cleveland and Eric C. Ward.

The Unions Merge

In 1932, the Southeastern and Southern Unions merged. After the merger, the Colored Department arrangement continued until December 1945, when the South Atlantic and South Central conferences were organized.

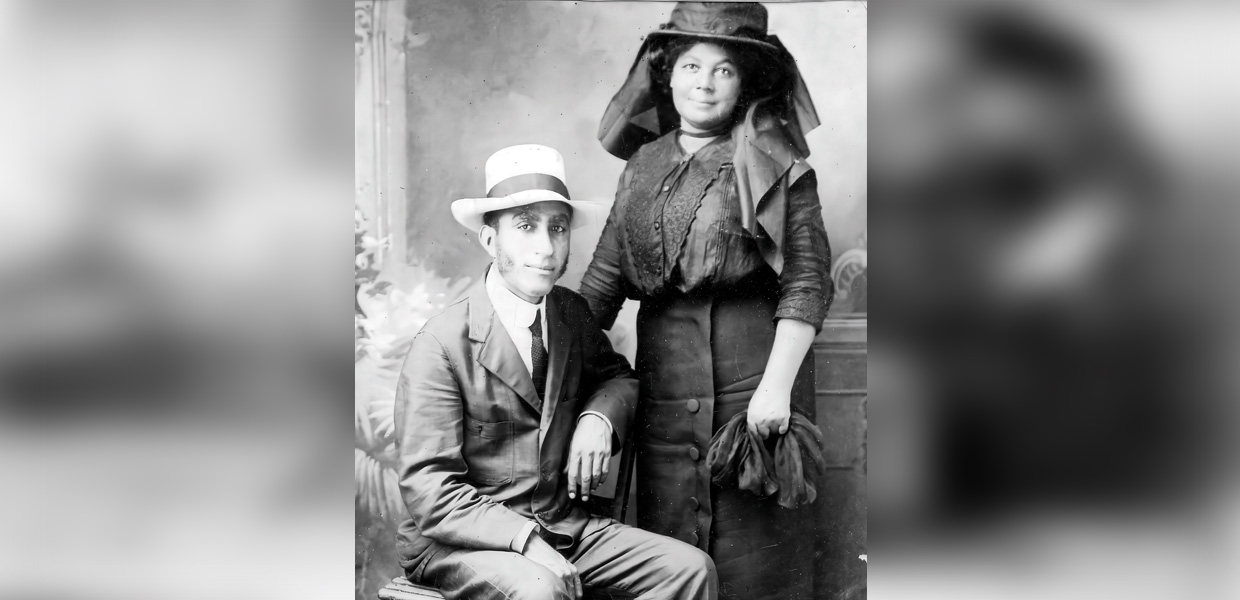

Anna Knight

Miss Anna Knight, the first Adventist missionary to India, returned to Mississippi before moving to Atlanta to serve as a Bible instructor with Pastor William H. Sebastian, who was sent to Atlanta to establish what is now known as the Atlanta Berean Church. Miss Knight was soon asked to serve the Southeastern Union as Home Missionary secretary (1915), then as Young People’s secretary (1917), Education (1919), and Sabbath School director. She held these positions until her retirement in 1945. In 1932, the Southern Union hosted a large Youth Congress for White youth on the campus of Southern Junior College. Anna Knight, recognizing the benefit such an event could have for Black youth, hosted a Union Youth Congress that Black youth could attend at the Berean Church in Atlanta in 1933. The following year, she hosted a National Youth Congress for Black youth on the campus of Oakwood in Huntsville, Alabama.

During this period, Black workers in the South expanded again with the opening of the Riverside Sanitarium and Hospital in Nashville, along with a missionary publication called Message (1934).

At the Union level, a secretary of the Colored Department was introduced in 1942, and John H. Wagner Sr. became the secretary of the Southern Union Colored Department. He was succeeded by Harold D. Singleton (1943-1945).

Regional Conferences

At the Pre-Spring Council of the General Conference held on April 8-10, 1944, in Chicago, Illinois, consideration was given to the question of whether to integrate the conference memberships, maintain the status quo, or form separate conferences. During the discussion, the Lake Union president, J. J. Nethery, made a convincing statement for separate conferences led by Black leaders (Pre-Spring Council Minutes, 1944). After this action, the Lake Region Conference in the Lake Union, the Allegheny Conference in the Columbia Union, and the Northeastern Conference in the Atlantic Union were organized.

Shortly afterward, the Southern Union formed a Colored Survey Committee to examine the possibility of establishing regional conferences in this area. After careful consideration, they decided to organize two conferences because of the vast size of the Union territory.

On Monday, December 3, 1945, 398 delegates from Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina gathered at Berean Seventh-day Adventist on Ashby Street in Atlanta, Georgia. They voted to form a conference, chose the name South Atlantic Conference, and approved their constitution, bylaws, and officers. The conference started with 3,300 members across 70 churches.

Hackman reported, “The following officers were unanimously chosen to serve during the next biennial term: President, H. D. Singleton; secretary-treasurer, L. S. Follette; Book and Bible House manager, L. S. Follette; Educational and Missionary Volunteer secretary, F. H. Jenkins; Home Missionary and Religious Liberty secretary, H. D. Singleton, Publishing Department secretary, Richard Robinson; Associate Publishing Department secretaries, Silas McClamb, W. W. Jones; Sabbath School and Temperance secretary to be supplied by the new committee; Conference Committee, H. D. Singleton, L. S. Follette, W. S. Lee, F. S. Keitts, W. W. Fordham, F. H. Jenkins, N. B. Smith, A. J. Bailey.” The following day, Tuesday, December 4, delegates from Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky met in the Government Community Hall in Birmingham, Alabama, and voted to establish the South Central Conference.

Hackman reported, “The South Central Conference will comprise forty churches, with a total of 2,300 members. The following workers were chosen for the various offices: President, H. R. Murphy; secretary-treasurer, V. Lindsay; Book and Bible House manager, V. Lindsay; Educational and M. V. secretary, Charles Dickerson; Home Missionary and Religious Liberty secretary, H. R. Murphy; Publishing Department secretary, W. E. Adams; Associate Publishing Department secretaries, B. H. Ewing, E. Brantley; Sabbath School and Temperance secretary to be supplied later; executive committee, H. R. Murphy, V. Lindsay, B. W. Abney, Sr., C. A. Lynes, J. G. Thomas, I. H. Hudson.” With the formation of these conferences, the Colored Department was dissolved in December 1945. Until this point, the Black members were in state conferences but were completely segregated. Integrated churches, schools, and camps would not begin to appear until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

These new conferences represented a different kind of organizational structure in two ways. They were called regional conferences because their territories covered multiple states. They were also unique because they were made up entirely of Black members, with Black leadership that for the first time held administrative authority. Also for the first time, Black leaders had a voice and a vote on the Southern Union Executive Committee and the President’s Council. These elected leaders also attended the General Conference and North American Division Year-End Meetings as delegates at large and were able to nominate Black leaders to serve at the union, division, and General Conference levels of the Church.

God has blessed the regional conferences in the Southern Union. By the end of 2024, the South Atlantic Conference had 155 churches and a membership of 36,750. The South Central Conference had 143 churches and a membership of 29,240. The Southeastern Conference reported 46,697 members in 158 churches (Adventist Statistical Report 2024, p. 10).

South Atlantic Conference (1946-2026)

Harold D. Singleton, who had served as the field secretary for the Southern Union Colored Department from 1943-1945, was elected to be the first president; he served from 1945-1954. Subsequent presidents were John H. Wagner Sr., 1954-1962; Warren S. Banfield, 1962-1971;

Robert L. Woodfork, 1971-1980; Ralph B. Hairston Sr., 1980-1988; Ralph P. Peay, 1988-1997; Vanard J. Mendinghall, 1997-2011; William Winston, 2011-2021; and Calvin Preston, 2021 to present.

South Central Conference (1946-2026)

H. R. Murphy, who served as evangelist and on the Colored Department committee for the Alabama-Mississippi Conference, was elected the first president and served from 1946-1954. His successors are Walter W. Fordham, 1954-1959; Frank L. Bland, 1959-1962; Charles E. Dudley, 1962-1993; Joseph A. McCoy, 1993-2005; Benjamin P. Browne, 2005-2009; Dana C. Edmond, 2009-2016; Benjamin Jones Jr., 2016-2025; and Furman F. Fordham II, 2026-.

Southeastern Conference Forms

By 1980, the South Atlantic Conference had become the largest conference in the Southern Union, with 21,959 members. A special constituency meeting was held on June 4, 1980, to consider dividing the conference. The delegates gathered and voted to split the South Atlantic territory into two separate conferences starting January 1, 1981. The lower territory, which included Florida and South Georgia, became the Southeastern Conference, with James A. Edgecombe as president. The upper territory remained the South Atlantic Conference, with Ralph B. Hairston as president.

As we move into the future, Calvin B. Preston, president of the South Atlantic Conference, says, “The catchphrase from years past remains just as relevant in 2025: ‘Souls and Goals.’ Evangelism and church planting continue to be the lifeblood of the Church, and fulfilling the Gospel commission stands at the forefront of our mission. The goals of prioritizing Adventist education — as well as children’s ministries, youth, and young adult ministries — ensure that those who carry the work forward understand that we have nothing to fear for the future except that we forget how God has led us in the past.”

retired Southern Union Conference communication director and historian.

Southern Union | January 2026

Comments are closed.